The Enlightenment philosopher John Locke lived through the turmoil of the Civil War and the hostility that followed it. In his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, he suggested that improved use of language could put an end to disputes and self-interest. In other words, if the definition of words could be agreed and misunderstanding avoided, peace would follow naturally. This is an example of rational idealism; it is, of course, the most incredible nonsense!

It shows that even an extremely intelligent Cambridge-educated philosopher, a giant of the Enlightenment, believed that language was more powerful than anything! It could rule life itself.

Locke was not the only one to think like this. He was a member of the Royal Society, founded in 1660 to promote science — except they didn’t call it science; they called it Physico-Mathematical Experimental Learning. They did their best to write as clearly as possible and avoid using unnecessary expressions.

At the time, scholarly books were usually written in Latin because Latin was the international language and was regarded as the best and most precise language. However, the Royal Society wanted to make English a language of scholarship.

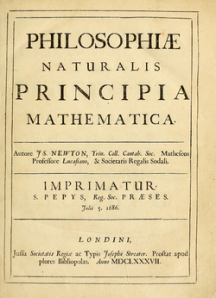

The great English scientist, Isaac Newton, had published his Principia Mathematica in Latin in 1687 but, in 1703, he published Opticks in English.

It was a new, rational way of writing in English which employed words in a new way. Some words, like refraction (1570s) and lens (1690s) were quite recent inventions. However, words like refrangibility, reflexibility, indistinctness, and well-defined were made up by Newton to help him explain clearly and he changed the meaning of some existing words like transmission (1610) and opaque (1400s) to fit his experiments. Scholars were changing the language to make it part of their apparatus (a word that first appeared in the 1620s).

By this time, printing presses were very common and daily newspapers were being read by ordinary people. People who wanted to feel fashionable (generally from the growing middle classes) met in coffee houses to read and talk about the news. Joseph Addison, who founded The Spectator (a Renaissance Latin word, by the way) magazine in 1711, said that the different newspapers reported the same stories in very different styles; visitors to the coffee houses would not leave until they had read every one of them. Of course, they paid for the coffee but not for the newspapers.

Although people really enjoyed the variety of reading materials, there was also concern that English might be changing in an uncontrolled way. Journalists did not have a Royal Society to protect them or a John Locke to guide them. There was a serious worry that English might become unrecognizable in a very short time.

The satirist Jonathan Swift, who wrote Gulliver’s Travels, complained that nobody would be able to understand anything a few years after it was written! Swift hated the way that the aristocracy spoke; they were careless and abbreviated too much. There was no point in relying on them to set an example. Swift also disliked newly fashionable words such as banter, bubble, shuffling, and sham, even though they have survived to this day. Swift wanted to control English and stop it changing, just as Latin and Greek had stopped changing.

Swift wanted an Academy, similar to the ones that existed in France and Italy, to fix and control the English language. People pointed out that the academies in France and Italy had failed but Swift was utterly determined. He went to see Queen Ann to make his case. Unfortunately, she died soon afterwards and was replaced by King George I who, as we know, spoke no English and could not care less about Swift’s plan.