Even after the Civil War and the Restoration, the King’s supporters (Cavaliers/Tories) and Parliament supporters (Roundheads/Whigs) continued to argue about who should make which decisions. The years of fierce debate gave English words to argue with. Words and expressions like Roundhead, Cavalier, plunder, iconoclast, cabal, regicide, Lord Protector, commonwealth, restoration, Papist, nonconformist, keep your powder dry, and warts and all made up a lexicon of faction and dispute.

Kings and queens were going to lose a lot of their power to politicians, but monarchs were still expected to be useful and also, if possible, be able to speak when required; eventually, royal families were expected to be model families.

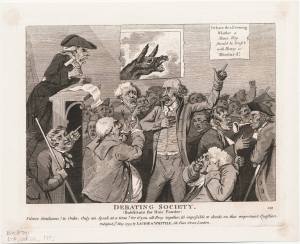

The English language culture of debate was to develop with a two-party (Whigs v Tories) system in Parliament. Debating Societies emerged in London in the early eighteenth century; men and women of all social classes saw great value in developing their debating skills.

The debating society at Cambridge University has run for longer than any other in the world; debate is still considered an essential educational tool in the British Isles. One of the things that has been debated ever since the Civil War is whether we really need Kings and Queens. How did the British monarchy survive with all these arguments going on around them?

When Charles II died, his brother, James II became king. James II was to be the last Stuart king. He was suspected of being pro-French and pro-Catholic. The leading nobles in England did not want a headstrong Catholic king who might interfere with their political aims.

Finally, the leaders of government in England called on James’s Protestant son-in-law, William III of Orange, to replace James II. William III invaded, and James II ran away. This was The Glorious Revolution of 1688.

New laws were passed making it impossible for kings or queens of the United Kingdom to be Roman Catholic. When William III and his wife, Queen Mary II (as well as Mary’s sister Anne, who succeeded them) failed to produce any children, another convenient European protestant family was found to provide the monarchs for the United Kingdom; this was the House of Hanover, the descendants of Princess Sophia of Hanover.

There were, at the time, about fifty Catholics with a stronger claim to be king or queen of the United Kingdom! Sophia was the granddaughter of James I, but more importantly, her family was solidly Protestant. Sophia’s son, George I, a German who spoke no English, became king; the Hanoverian dynasty began with him. Although the power and freedom of British monarchs has been limited, there has been great continuity since then.

The last British monarch of the House of Hanover was Queen Victoria, who died in 1901. Her son and successor, Edward VII, belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the line of Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert.

George V changed the name of his branch from Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to Windsor in 1917 because of anti-German sentiments during World War I.

The United Kingdom today, of course, is the Protestant parts of the British Isles: England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. In the United Kingdom’s constitutional monarchy, kings and queens have limited powers, and are expected to follow strict guidelines. As Britain becomes more modern, royalty becomes less and less important.

However, even though the United Kingdom has a constitutional monarchy, with Parliament making the important decisions, the monarch is still expected to behave well and even speak on occasion.